The Future of Our Planet is in Our Hands

We can’t afford to feel overwhelmed or hope that someone else will address our environmental problems. Stories can be transformative and galvanize the meaningful actions necessary for inspiring change.

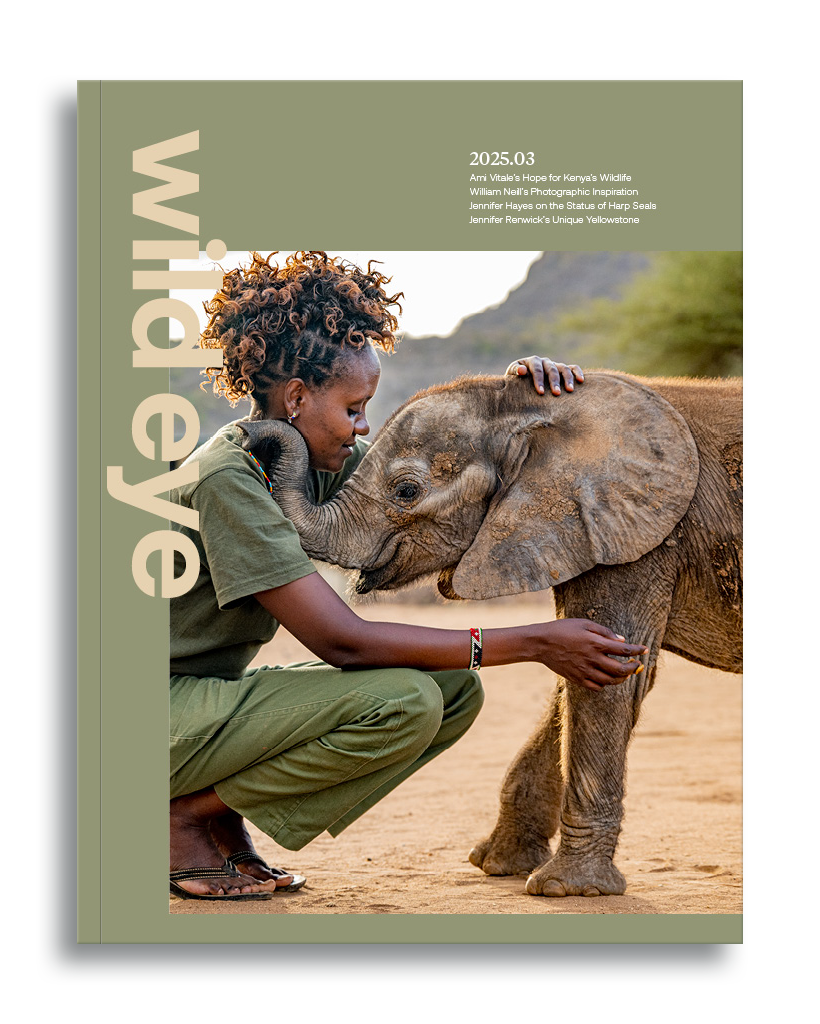

↑ Magdalen Island, Gulf of St. Lawrence A harp seal pup called a “white coat” seeks shelter from the relentless winds that scour the sea ice nursery. When mothers return to nurse their pups, they become a living, warm, wind-barrier.

Words and Images by Jennifer Hayes

As a teen growing up on a dairy farm in upstate New York, I had one framed poster on my wall. It was a harp seal photo by Bob Talbot.

I somehow managed to acquire it in a pre-Amazon world, and I must have wanted it badly because I didn’t have extra money kicking around. That photograph followed me to my college dorm. I’ve learned something over the years: Image makers have influenced others, long before the word “influencer” landed in the Oxford Dictionary as an occupation.

Without knowing Bob Talbot, or what a wildlife photographer was, his work found me. Staring at his photo of the harp seal pup under a bright blue sky, somewhere in the fabled North, I could only dream of what it might be like to journey there and meet these incredible creatures. But surely it was a job meant for others, not a kid on a farm. His image subtly, very subtly, might have opened the mental door of possibilities in my mind.

The sun bounced off a soft blanket of freshly fallen snow under a cerulean blue sky. The wind, a constant low vibration and cello-like sound, delivers a chorus of infant cries across this frozen world.

A newborn pup, its coloring still tinged with a soft hint of yellow from amniotic fluid, was content and protected from the wind. It nestled inside a small snow cave molded by body heat and movement. When it turned again, I could see its thick pink placenta. It had only just been born. I heard sloshing water and short grunting breaths before I saw a whiskered face with big dark eyes rise and survey the surroundings from a nearby hole in the ice.

The female emerged using long curved claws to pull herself onto the ice and across to her pup. They met with a nose-to-nose kiss of recognition that establishes kinship. Are you my pup? Are you my mother? The female turned to gauge my presence, determined I was no threat and settled onto her side, shutting her eyes as the pup began to nurse.

Welcome to the harp seal nursery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence near Magdalen Island, Quebec, the southernmost of three Northwest Atlantic harp seal whelping grounds. Adult seals migrate here from the Arctic in November, the pregnant females searching for suitable ice on which to give birth in February.

Harp seals are an “ice obligate” species; a fancy phrase that means they require sea ice to survive. The Gulf of St. Lawrence pups are born on ice in late February and will nurse for 12 to 15 days. Their fat reserves will be critical to their survival when the mothers leave the ice for the final time to mate and then migrate back to Arctic waters. The abandoned pups must learn how to swim, eat, and be harp seals — on their own. If the pup survives this critical and most challenging phase of its life, it can expect to live 25 to 35 years.

White coats are one of the most captivating creatures on the planet with their onyx eyes, charcoal nose, and embryonic white fur called “lanugo.” Older pups, born days earlier, have the distinct advantage of time on their side. Every day spent on the ice is a day closer to survival. The climate is changing, and the harp seal’s world of weather is becoming increasingly unpredictable.

Pups need several weeks of stable ice to survive their infancy, in a world where the ocean is warming and spring comes earlier every year, and with it, increasingly strong storms that demolish the pack ice like a blender. A life born to ice is difficult, and natural mortality is high. Now the pups face a new challenge: climate change. Multiple years of increasing air and sea temperatures and decreasing ice have put the Gulf of St. Lawrence harp seal population at risk.

There’s no “normal” shore-to-shore ice now. The problem isn’t that the ice is melting. It’s not forming to begin with. I’ve spent years poring over winter ice charts and emailing with Canadian climatologist Dr. Peter Galbraith, predicting, planning, and looking for ice. With few exceptions, every year looks bleaker than the last.

The Magdalen Islands resemble a ship at anchor in the center of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and I recommend that you find your way there someday. My first 2011 trip began as a National Geographic assignment with my partner David Doubilet to document the Gulf of St. Lawrence marine ecosystem.

Our boat was an ice-worthy fishing vessel. Magdalen Islanders have hunted seals here since the 1600s. There has been a substantial decline in the number harvested commercially due to a shrinking market for seal pelts, but when ice conditions allow, some seals are still hunted for subsistence use, medical research, and a limited Canadian commercial market. The great historic — and controversial — hunts that ranged into a few hundred thousand seals are, for now, a thing of the past.

Pushed by wind and current, the ice pack was a moving target, and it finally took the Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) helicopter to guide us onto the ice pack. Our seasoned captain nosed the boat into a patch of sea ice supporting a herd of over 10,000 seals. We drifted with the ice day and night, photographing seals above and below the ice.

During the day, sunlight shimmered across the icy expanse, where harp seal mothers nursed and rested with their new pups until nightfall when a chorus of infant-like cries drifted through the hull of our boat, lulling us to sleep.

It’s extraordinary to walk among this pulse of life on the ice and then put on a dry suit and enter the seals’ world with a camera. Sliding beneath the nursery, I was surprised to hear thousands of seals communicating with grunts, barks, chirps, bellows, and long trills. It’s indescribable.

Life at the ice’s edge is busy. Mothers come and go beneath a ceiling of ice pierced by shafts of light. Apprehensive white coat pups peer into the sea, contemplating their first swim while mothers spy-hop through the ice to check on their young from a distance. Pups just a few days older test their swimming skills and learn what it is to be a harp seal.

Despite the challenge of finding the herd, the assignment was a photographic success, and it gifted me with a thought-provoking moment in the ice, especially meaningful because I’m a born skeptic about stories of human–wildlife interactions. On our last day of snorkeling in the ice, I was photographing a mother and pup. A male seal nipped at both ankles and then scrambled up my body and over my back, pushing me beneath the surface and dislodging my mask.

During the day, sunlight shimmered across the icy expanse where harp seal mothers rested beside their new pups, fur as soft as clouds, with obsidian eyes and charcoal noses.

As I reached for the sinking mask, I felt a swoosh of water as the mother harp seal dove past me and beat the crap out of the testosterone-filled male. She surfaced slowly and swam 360 degrees around her pup. Once satisfied her pup was safe, she used her head and body to gently nudge and guide both the pup and me through the water toward the safety of solid ice. We reached the edge of the pack where I watched the mother and pup climb through an opening.

My mind was racing and my hands were near useless from the cold. I was finning to lift my SEACAM housing onto the ice just as a male came beneath the ice ledge and bit my groin, let go, and bit my right thigh. In a nano-second, I had jumped onto the ice wearing my heavy weight belt — a feat I thought was impossible. Turns out it’s possible to practically teleport out of the water when properly motivated. I know exactly why the male challenged me: I was swimming with a female, and I was competition. I can’t say that I know why the mother seal nudged me to the safety of the pack ice with her pup. I can say I’m a skeptic no more.

A fast-moving storm forced us to get underway. A low-pressure system tore through the gulf, whipping it to a frenzy. After 30 hours, we made our way to port. I was stepping off the boat when the captain said, “I hope you have all you need. They’re gone.” Confused, I replied, “Gone?” He nodded. “The ice is gone, smashed, along with the pups.” The nursery collapsed in the storm, causing a catastrophic loss. I stood silent in the parking lot, trying to comprehend that the pups we had worked with now existed only on our hard drives. It was a pivotal moment, and I was resolved to return to tell their story of thinning ice.

Our initial assignment was published in National Geographic as “The Generous Gulf” in 2014, but our commitment didn’t end with the pages of the magazine. I return to Magdalen Island each year that the ice allows and collaborate with the DFO research teams to learn ice coverage, herd size, and annual pup mortality. In 2022, I joined Dr. Gary Stenson and his team aboard the Canadian Coast Guard ship, Sir William Alexander. We embarked on a month-long harp seal survey of the largest harp seal whelping grounds in the western Atlantic off the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador. This whelping area is called “The Front” and is known for big seas, big ice, a million-plus seals, and the great historic seal hunts. But not any longer as the ice is declining here, too.

For several years, the world of the harp seal wasn’t just accessible to professional photographers and filmmakers. Magdalen Island, uniquely suited for access and travel to the harp seal nursery, became a special place on the planet where anyone could put on a float suit and helicopter out to experience this pulse of life. Sadly, because of declining ice conditions, the Magdalen harp seal ecotourism operation shuttered in 2024, a record year for high temperatures.

Where are we in this harp seal story that began 14 years ago? I recently returned from Magdalen Island on March 30th, 2025. The winter for many Northerners resembled the good old days — cold and snowy. I had hopes for ice in the gulf. Despite the cold temperatures, very little ice formed.

Consecutive years of record-high temperatures allowed the gulf to rise 5-plus degrees throughout the entire water column. Below-freezing temperatures weren’t enough to form sea ice where it should have been. Desperate females searched the gulf for ice. Some made their way to the shores of Magdalen and gave birth to their pups on sand beaches and abandoned them. Others birthed at sea, and some swam north for the Strait of Belle Isle searching for patches of ice.

I parked my car and walked to the beach. I searched for white coats that were easy to miss among white clumps of ice at the waterline. Wind, waves, rising tides, sand, houses, and beachgoers were an alien habitat for the starving pups. They were thin, exhausted, and weak. I spent the day and into the night trying to adequately tell their story. I left at 4 a.m. to charge camera batteries, download photos to hard drives, and find caffeine. I returned at sunrise and saw ominous clusters of gulls on the beach. The young seals I left 3 hours earlier had been killed by coyotes. Once again, the pups I had worked with now lived only on my hard drives.

We’ve passed the tipping point in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In an ironic twist, scientists suggest that zero ice is better than weak ice, which tempts the females onto an unstable nursery that will ultimately collapse. Their reports indicate harp seals will follow the retreat of ice northward towards the Davis Strait.

I’ll follow the story of the harp seals as the charismatic face of climate change. As seas warm, southern ice nurseries are vanishing beneath the pups and in front of our camera lenses. The good news is this species is circumpolar and its global population still numbers in the millions.

As the Gulf of St. Lawrence herd ages and fewer pups are born in the Gulf, this population will slowly lose the genetic memory of their migration route, and the survivors will retreat northward. Like them, I’ll follow the ice wherever it leads.

See more of Jennifer Hayes’ work at www.jenniferhayesimages.com.

Explore this Issue

Complementary Article. Subscribe for Full Access.