Share

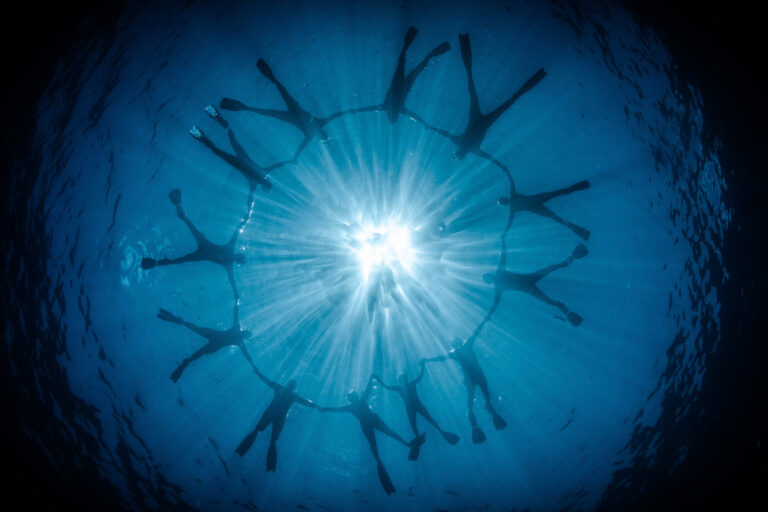

↑ White rhinos make a fierce silhouette against the backdrop of a raging fire.

Words and Images by David duChemin | February 2025

I arrived at Solio Game Reserve on February 21, 2025, to spend three days photographing rhinos. Sitting on the plains between Mount Kenya to the east and the Aberdare range to the west, Solio has a population of 250 rhinos, both white and black, on its 20,000 acres. Solio is a paradise, and it was there I learned to love these unlikely creatures.

Reputed to be grumpy and stand-offish, I’ve found rhinos to be mostly gentle, curious, and timid. In the case of the white rhino they are near threatened. According to the World Wildlife Fund, only 27,000 rhinoceros remain in the wild, almost all of them in sanctuaries and parks of one kind or another where they are protected from poaching and habitat loss.

When I arrived at Solio, the air burned my eyes and throat, and the smell of smoke was on the wind, the result of a controlled burn on sectors of the sanctuary and ranch designed to mitigate the spread of invasive hydrangea. By the time I had stowed my gear and was out on my first game drive, it was clear something was wrong. My guides were more active on the radio than usual, the smoke growing thicker by the minute. By 8 p.m., the sun had set and the flames stretched for what looked like several miles, bands of red and yellow that leaped and danced, moving ever forward with the winds. I was both mesmerized and nervous.

Watching the rhinos silhouetted against the flames through my 300mm lens, it was hard to make much sense of my emotions. It was all just so…beautiful. Fascinating. I was reminded of an exhibit by photographer Edward Burtynsky entitled Terrible Beauty. It was, all at once, a thing of terror and beauty. It was a heartbreaking juxtaposition and one that seems more and more symbolic, most especially when framed against the fires in Maui in 2023 (the most deadly in modern U.S. history), and the devastating fires in Los Angeles in January 2025.

The drought that made this fire possible, and hard to contain (which it was), was a result of expected seasonal rains that didn’t come. Increasingly, the once-predictable cycles of rain and drought are less and less predictable. Whole rainy seasons fail to arrive. And when they do, the baked ground is unable to absorb it, and the resulting flooding strips the earth of its topsoil. For years I’ve heard the same thing from pastoralists and farmers from Kenya to the Ecuadorian Andes: something is changing.

Something is changing on this planet on which we depend and there is no more powerful symbol of that change than fire. I didn’t make this photograph to make a statement, I made it as a response to something in me that couldn’t look away. I was too busy making photographs to also be processing the symbolism. But I see it now. I feel it now.

For more of David DuChemin’s work, visit his website: https://davidduchemin.com/

Get Annual Subscription